Wide-format Printing: How the sign industry was revolutionized

Addressing tradition

Gerber’s company also transformed signmaking and outdoor advertising. Until the 1970s, most signs were made the same way they had been for centuries, with paintbrushes, chisels and other hand tools. ‘Letterhead’ artists in small sign shops painted or carved letterforms and illustrators known as ‘walldogs’ hung from roofs on a scaffolding, holding a sketch in one hand and a paintbrush in the other. Within a decade, however, the outdoors saw swaths of high-fidelity vinyl images.

David Jopson Logan, who had a technical role with Gerber’s company, embraced the idea of making signs because his group understood lettering from their experience with computerized drafting machines. Dan Sullivan, an engineer, visited sign shops with Logan’s support and stood for hours observing sign painters executing their tasks. The creation of custom signage, he reported back, was an art form.

Most sign painters’ repertoires derived from a few memorized fonts, so they had to copy letterforms for complex typefaces from style books. For that process, a sign painter would place a projector on a table across from a sheet of paper posted on a wall and trace the image of each letter. To lay out the sign, he or she would string the characters together with appropriate letter sizes and correct spacing, which could mean hours of measuring and adjusting.

After completing the tracing, the sign painter would transfer the pattern from the paper to the sign surface. This technique, known as pouncing, entailed perforating the paper along the tracing to define the pattern as intermittent holes, then placing the paper on the sign surface and blowing chalk over the perforations, so the pattern was transferred as chalk dots. Finally, he/she would paint the sign within the outline of those dots.

Logan realized he could digitize those fonts, put them on a floppy disk and use a dot-matrix printer that created an image by moving the printhead in a serpentine ‘raster’ motion like a typewriter guide. The machine would allow the user to type the desired message into the computer and print the properly sized and kerned outline of the message on paper to be pounced.

After receiving favourable feedback on the idea from sign shops, Logan and his team began working on a prototype system, which included digitizing two fonts, writing software to scale and kern and mounting the pattern printer together with a small computer on a wooden plank.

A twist in the plot

One day, a local sign painter, Gordy Longmoor, saw the prototype. Sullivan asked his opinion and he said it would be better if, instead of printing letter outlines, it “cut them out of vinyl.” He explained that although most signboards were painted, some began as adhesive-backed sheets of vinyl, loosely bonded to a carrier liner. By scoring the vinyl sheet in the shape of the pattern outline and then removing (weeding) the excess material, the signmaker was left with an image in vinyl. The signmaker would then cover the separate characters with a wide strip of transfer tape, lift the tape that held the characters in fixed orientation and transfer the vinyl-on-tape construction onto the sign surface. Removing the tape left the vinyl graphic on the surface.

Longmoor asked whether a machine could be made to cut the outline of a letter. The engineers said there was a name for such a machine: a plotter.

Logan’s team had already invested three months in developing the raster printer prototype and, furthermore, the vinyl cutting plotter had drawbacks; the image would be limited to the colours of the available sign vinyls and some manual steps would be necessary, such as weeding the excess vinyl from the cut graphic on the liner sheet. Still, the method seemed viable. An automated vinyl cutter would allow users to compose characters quickly in various fonts, sizes, arrangements and appearances. A small drum could move the vinyl web back and forth as a knife carriage slid crosswise over it in co-ordinated motion. It would be simple and inexpensive. Logan assembled his team on a Monday morning and announced he was cancelling the raster printer project. By noon, they had started designing and building what became the SignMaker.

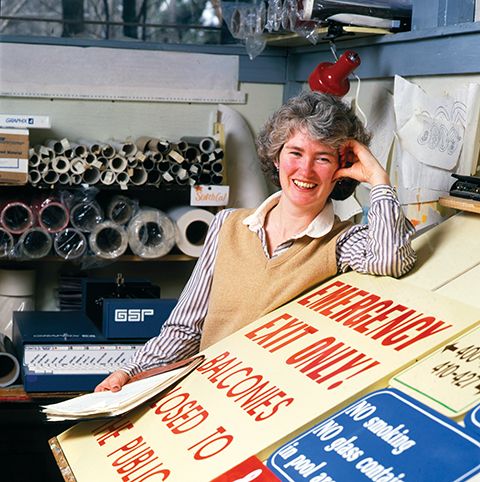

Sign shops were captivated by the machine, with its screen for previewing text, selection of font modules, keyboard to input, size and kern characters and small, lightweight console, which could be taken to a sign site in the trunk of a car. The vinyl that ran through the machine was 381 mm (15 in.) wide and perforated along the edges with holes that fit onto sprocket pins in the machine’s feed rollers.

The initial production run in 1982 sold out on the first day. Eventually, cumulative sales of the machines would top 30,000 units around the world.

The SignMaker changed sign manufacture from a paint-and-paintbrush system to one based on computers, data, plotters, scanners and vinyl. Because the signs were inexpensive, they became ubiquitous.