Meet the Maker | Chad Croissant: ‘Codes are the minimum—they work better as a floor than a finish line’

Hello, readers!

Welcome back to Meet the Makers, a series that takes a playful, engaging approach to showcasing the personalities and expertise of sign pros while staying rooted in the signage industry.

This week, we are featuring Chad Croissant, co-founder of BES+D (Built-Environment Signage & Décor).

Educated as a product designer, Croissant spent close to 30 years in modular building manufacturing, with a role centred on code compliance and detailed technical design. He managed teams supporting manufacturing and field operations for the construction of roughly 15,000 modules that became single-family homes, hotels, condos, and workforce housing across Canada and parts of the United States.

By his own admission, he never thought about signage until sidestepping into a partnership in a regional sign and print shop. Working with project managers from this new perspective, Croissant observed how often interior signage felt like an afterthought. Helping his former employer pursue the Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification for one of their projects offered another revelation.

Those insights led to co-founding BES+D (Built-Environment Signage & Décor), a company that supports design teams and project managers by engaging early, simplifying coordination, and aligning with complex construction schedules. The goal: creative interior signage for multi-unit residential buildings that contribute to environments supporting people where they live.

Here are his responses to our five offbeat questions:

What’s your sign superpower?

Seeing constraints as a gift.

Regulations, material limitations, and site conditions are easy to see as obstacles, but they’re more productive as design inputs that force thinking past obvious answers.

The cheat code: start with an intimate understanding of the rules of the game. I spent decades managing building code requirements across jurisdictions. That work taught me you can’t work creatively within constraints unless you understand their intent. When you can dig up why a rule exists, you can bend it on purpose—and also, have a thoughtful answer if an inspector asks.

What’s the most challenging project you’ve ever worked on?

An unexpected one: it started with a German train manufacturer and ended with affordable housing.

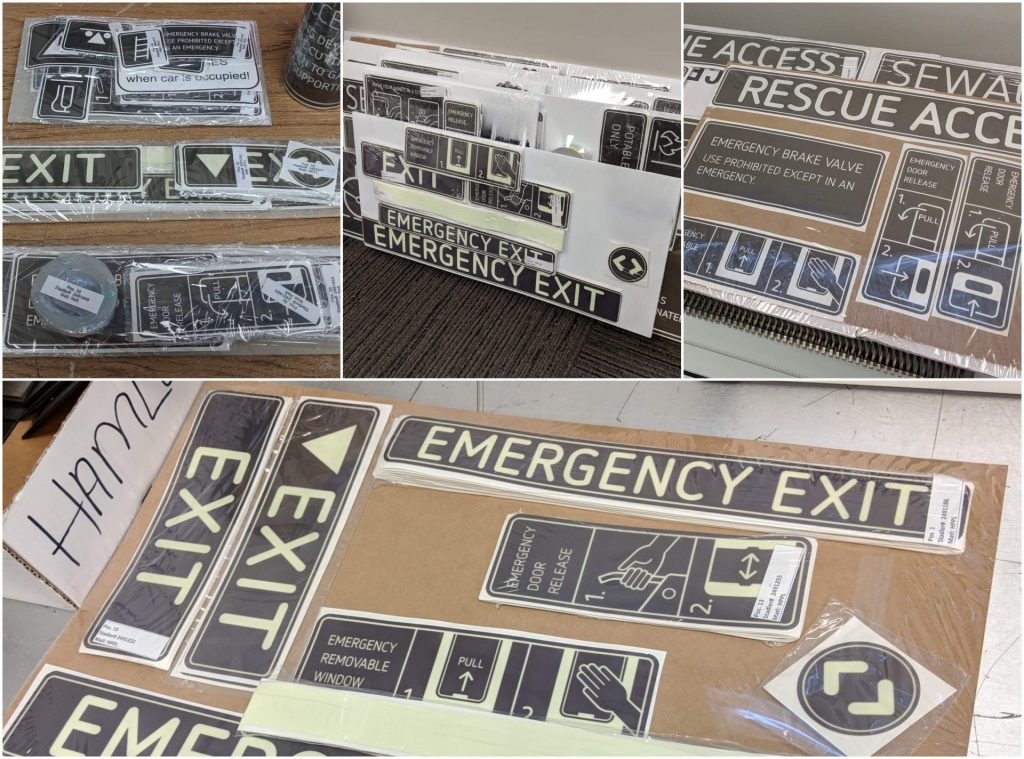

A prominent rail tour company had purchased new multi-million-dollar trains from Europe, but supply chain issues left them short-shipped on some safety and regulatory signage. The challenge: we needed photoluminescent and retro-reflective materials that met strict rail safety standards and could be digitally printed. Simple, right? Except it was like looking for a needle in a haystack. Plenty of glow-in-the-dark products existed, but none were tested to the required standards. Fortunately, our industry has some great trade shows. After limited success with web research, we ultimately found what we needed through a lot of face-to-face conversations at ISA Sign Expo.

Then came the logistical puzzle: co-ordinating with the project manager in Germany meant figuring out international calls, translating purchase orders to English, and timing a delivery to their production facilities before the remaining train cars shipped. Great people, interesting challenge—and materials that paid dividends later.

What’s a favourite sign/sign system you’ve worked on?

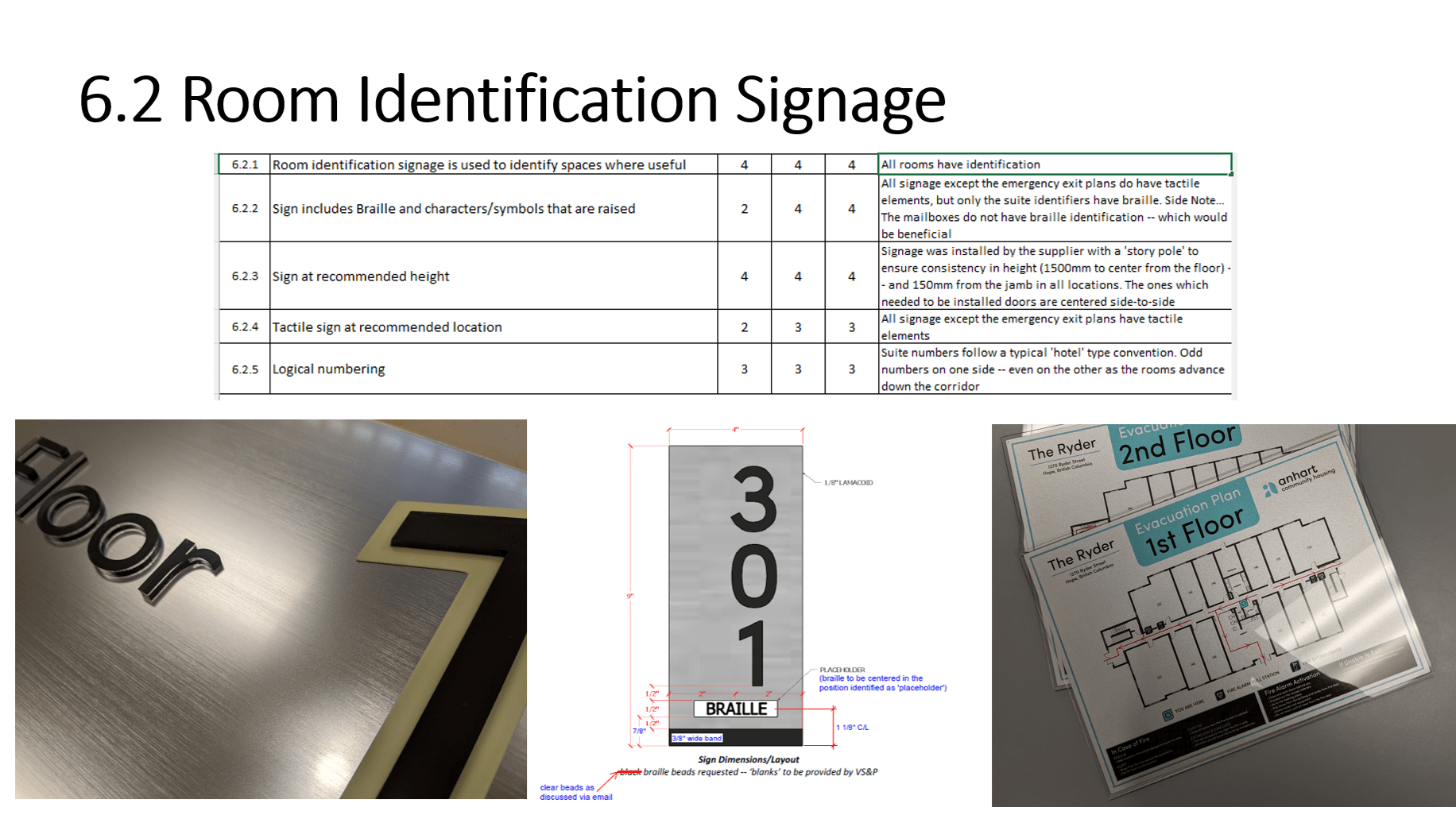

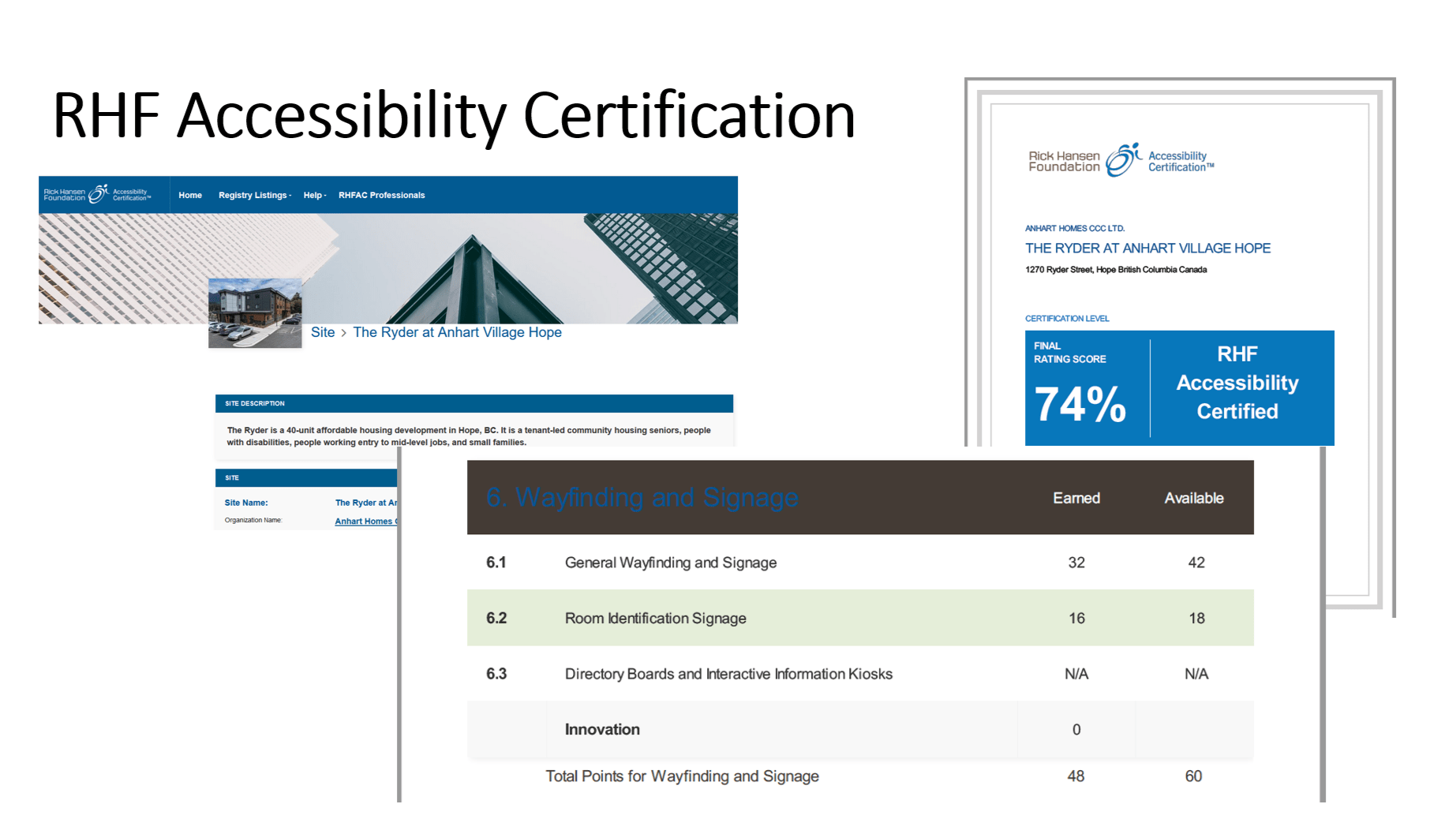

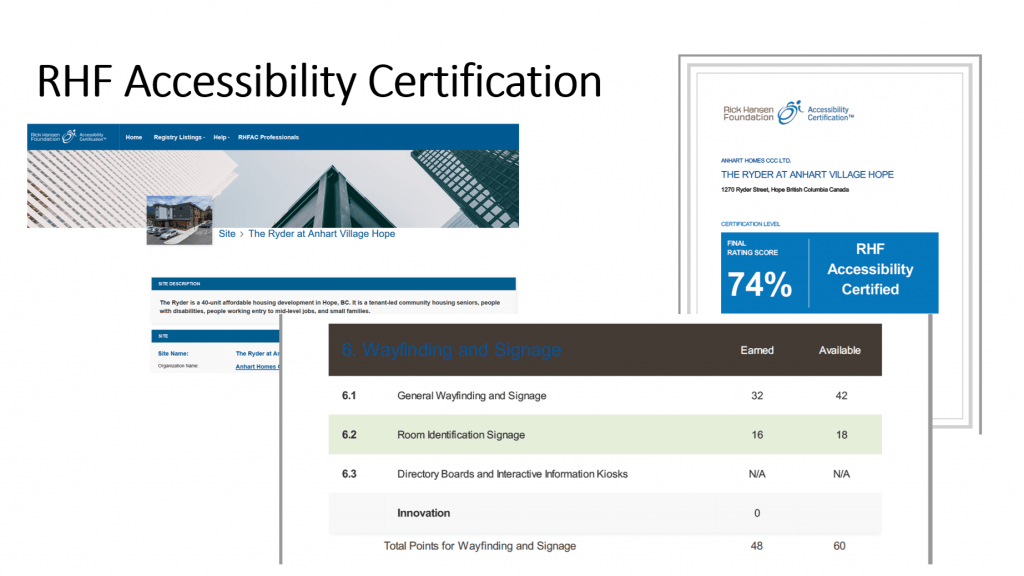

Interior signage for “The Ryder”, a 40-unit affordable rental building in Hope, B.C.

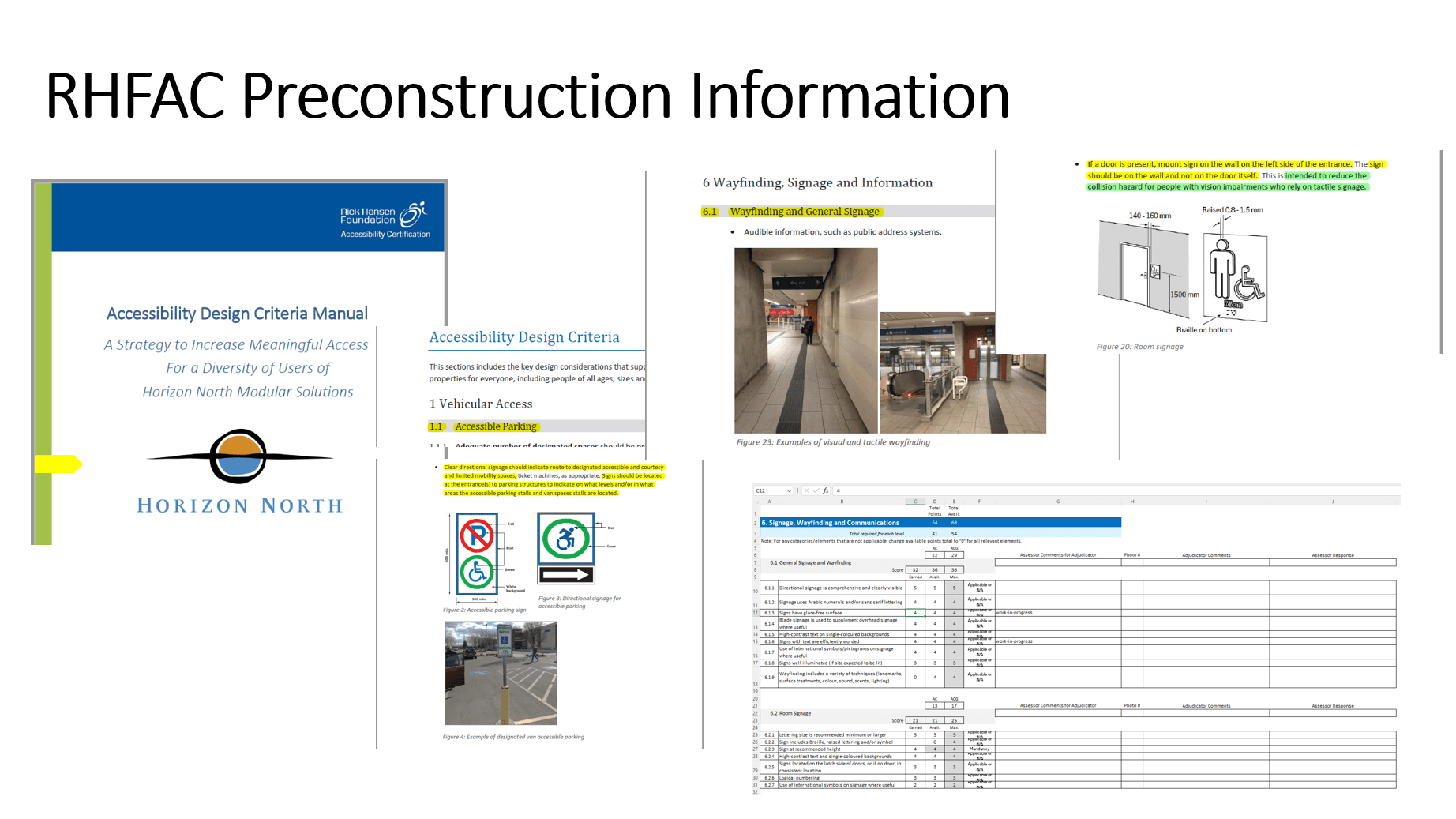

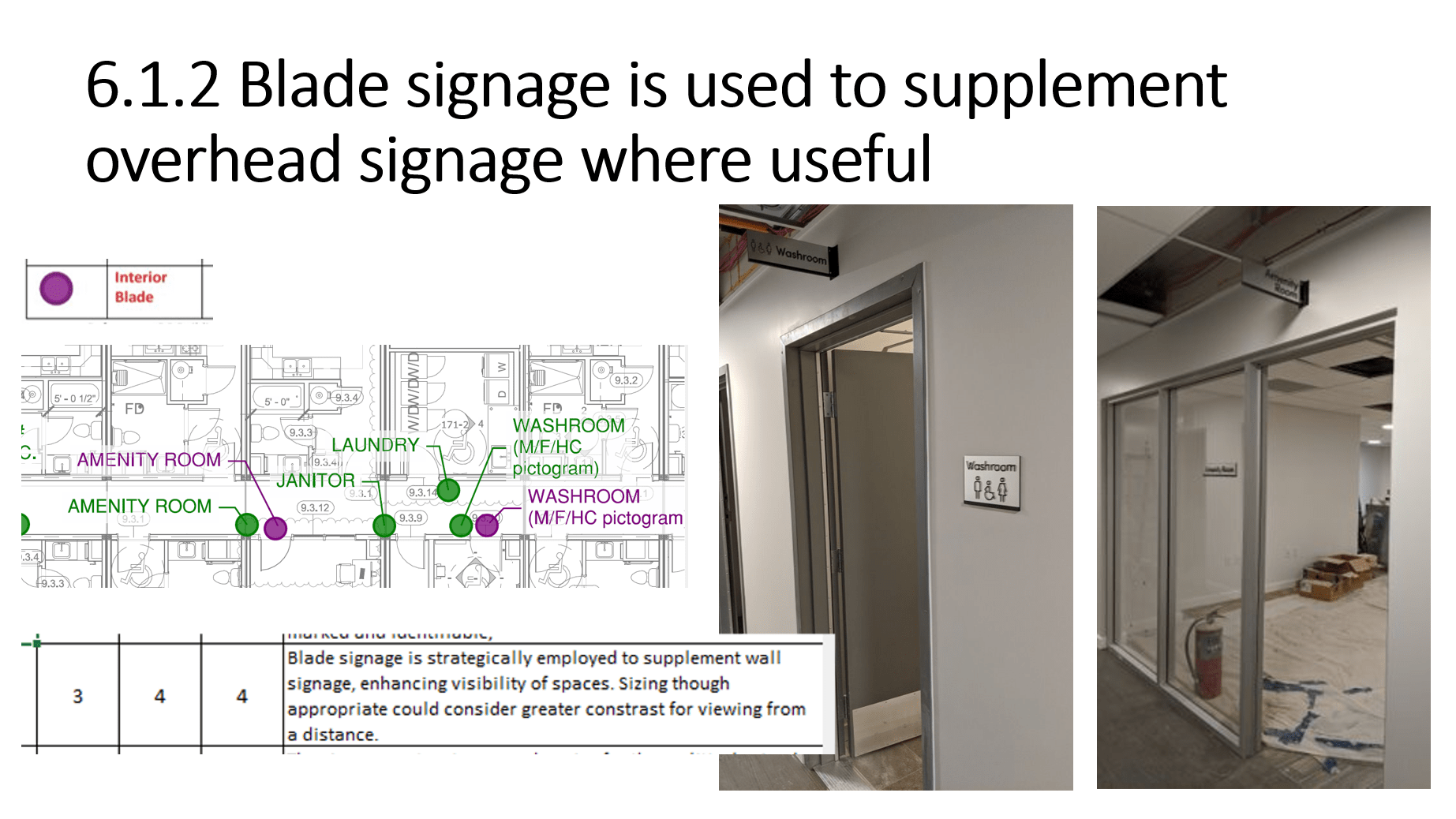

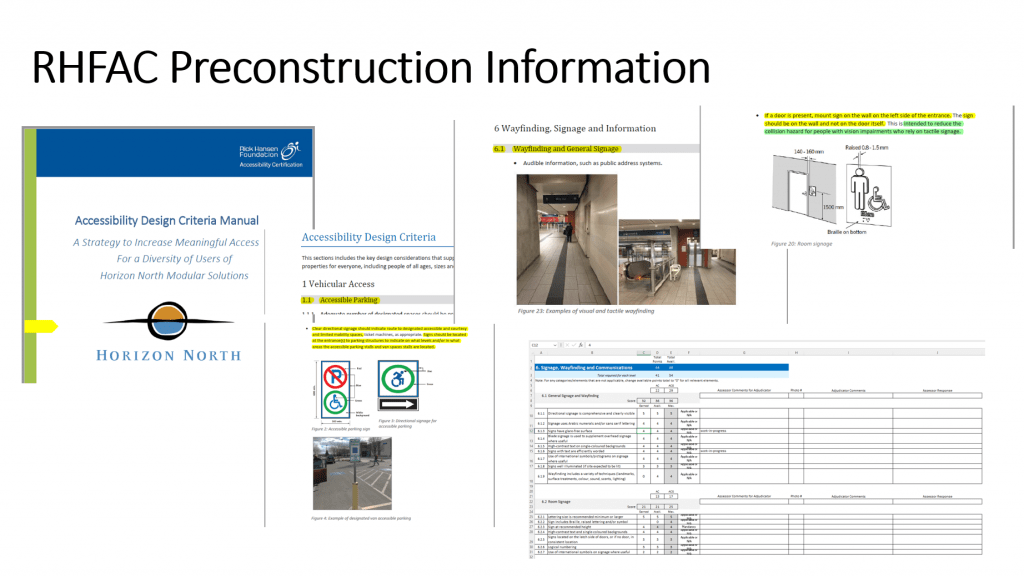

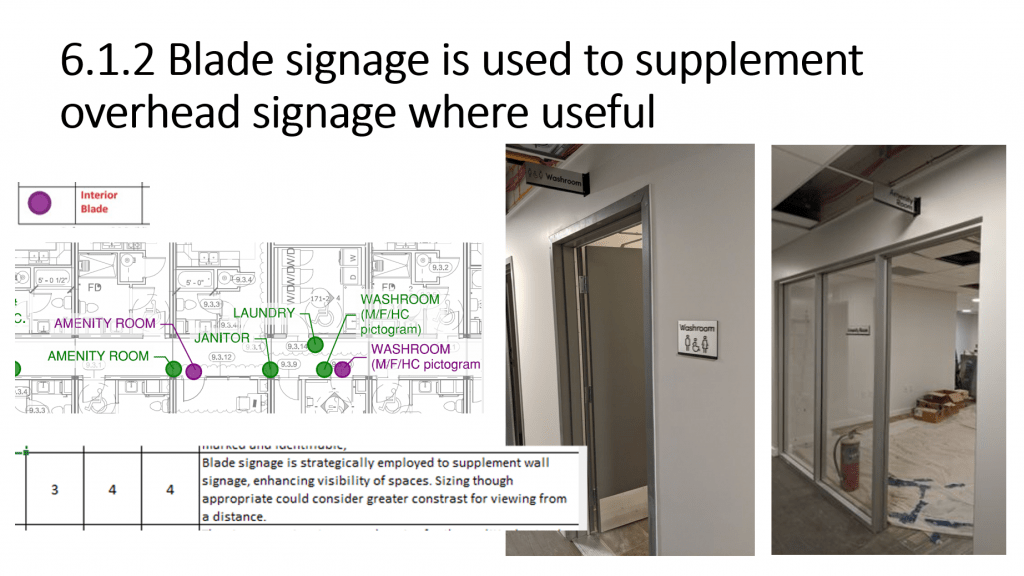

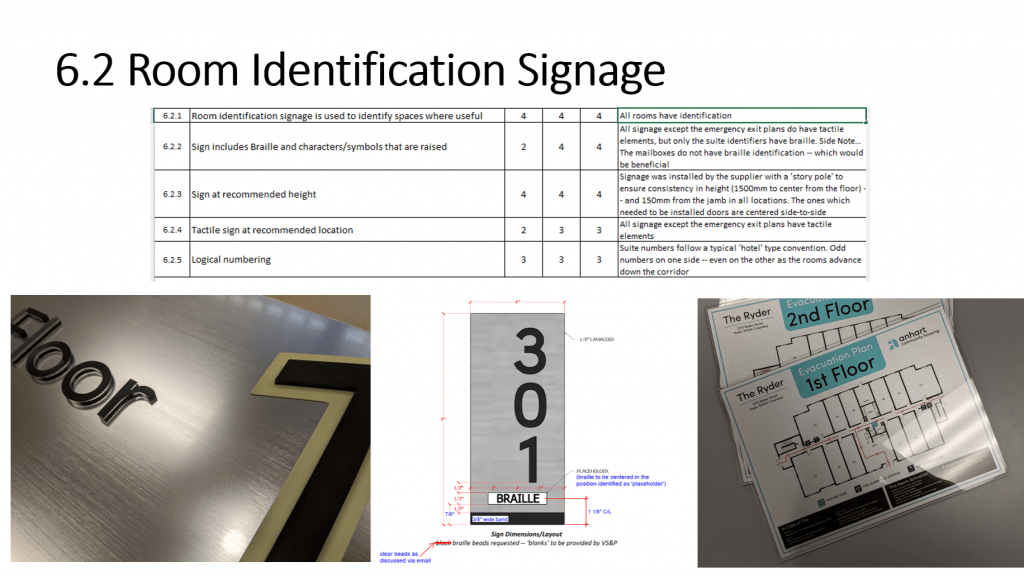

My former employer brought us in to handle the interior signage for the project. The owner was working toward the Rick Hansen Foundation Accessibility Certification (RHFAC), which was completely new territory. I thought I understood accessibility, but it turns out I only had a handle on compliance.

The RHFAC framework isn’t a checklist—it’s a set of “meaningful access” considerations. Remember those photoluminescent materials from the train project? One of the accessibility best practices suggested glow-in-the-dark material in wayfinding. Given the material validation we’d already done, and no building code requirement to derail us (pun intended), we incorporated it into stair level identification.

The favourite part, though, wasn’t the material or the finished signs. It was the start of a shift in perspective about who we design for, and who we might be forgetting.

If signage could talk, what’s the funniest thing it ever said?

“Hey, what about me?” But I guess it was probably the blank walls that were upset.

I spent decades working on buildings where I never thought about signage. We’d pour significant effort into interior layouts, mechanical systems, and highly detailed assemblies—then tack on whatever room numbers and stair signs were available at the end.

Now the ghost of signage future only occasionally taps me on the shoulder to remind me: “You missed a spot.”

What’s the one piece of signage advice you wish everyone knew?

“Compliant” is a dangerous word.

Codes are minimum standards, but often they work better as a floor than a finish line. The Rick Hansen Foundation has a useful phrase: “beyond code”. I initially heard that as “spend more” but now think of universal design as just another set of constraints to unlock, often using the same materials—varied execution.

We’re very much in the middle of figuring it out. The details are messy, and there are times when even well-intentioned efforts fall short. But that’s also where a lot of the learning lives: listening to people with different lived experience, adjusting the approach, and trying again.

The Accessible Canada Act and emerging model standards will soon give us a stronger nudge. My advice: start exploring now and be willing to go a little deeper than what current codes require.